Why the World Is So Pessimistic

How Disconnection and Misconnection Are Driving Our Civilization Crazy

Q: Is there any shred of optimism we can hang onto?

This is a deep question. I want to give it the respect it deserves. So buckle up for a weekend long read and deep dive.

To answer this question well, first we need to ask the opposite one. Why is there so much pessimism? You see, the accusation, these days, of “doomer,” hangs heavy in the air. But it’s a way to ignore a fact which is inescapable to a thinking mind. There’s a tsunami of pessimism sweeping the globe.

America’s incredibly pessimistic. Ask Americans “do you think your kids will have a better life?” — a way of asking “do you think things will get better over the long run” — and 80% of people say no. Just 1% of people say the economy’s in excellent shape. But America’s hardly alone. Pessimism’s sweeping Europe, too. What percent of Europeans do you think say their family’s lives will be better in five years? Just 20%.

What’s striking about that number? It’s the same percentage as in America. So in a sense — maybe a crude one, but still a real one — Americans and Europeans are almost as pessimistic as one another.

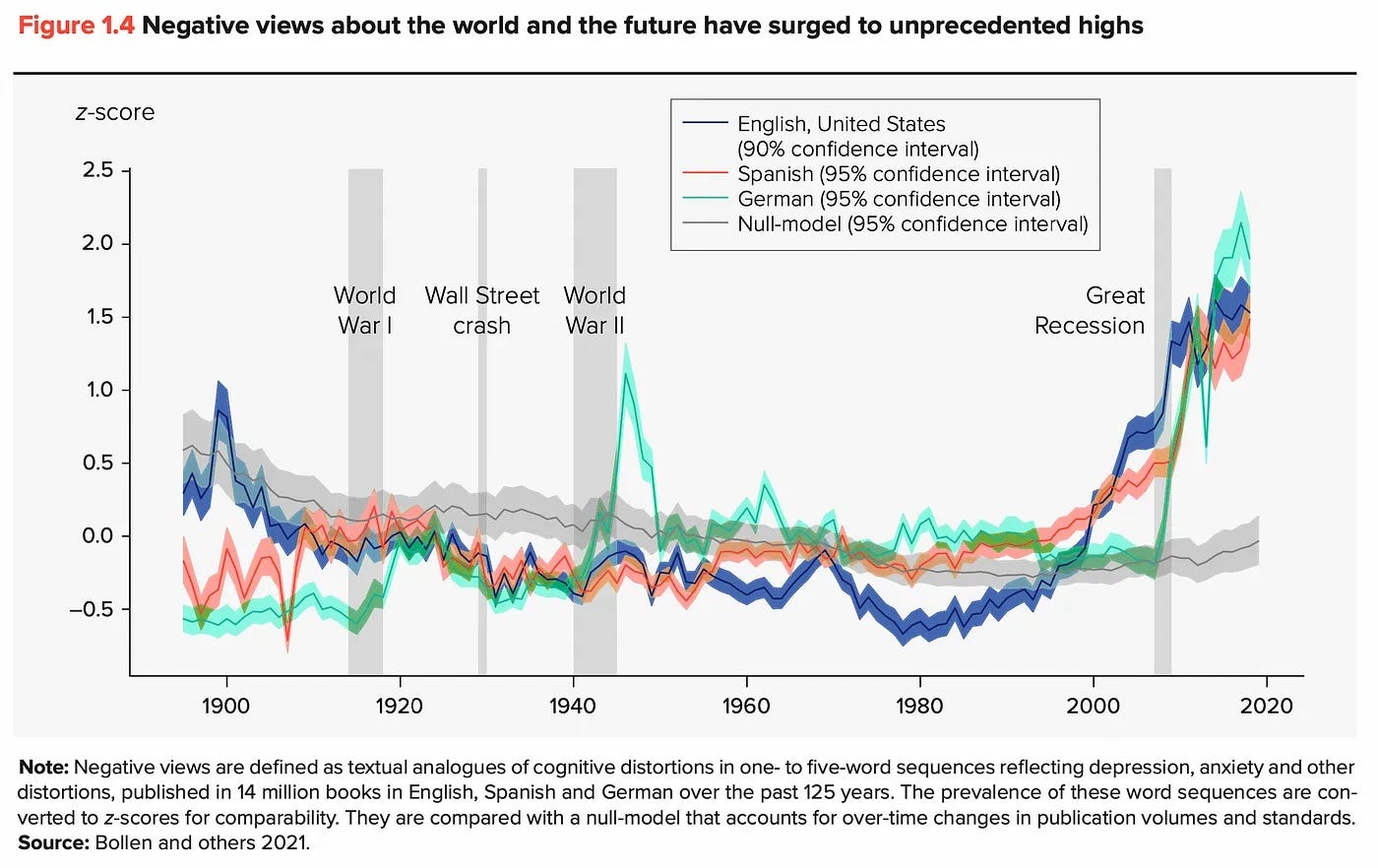

And that’s hardly the end of it. People around the world are more pessimistic than in a century. Sure, that’s very macro-level research, and it comes with caveats, and so on. But the results while they may be off by a few percent here and there — the trend is very, very clear.

So. Why is the world — from America to Europe to Asia and beyond — so pessimistic? Why is there is a tsunami of pessimism racing around the globe? After all, if you ask pundits and their ilk, famously, LOL, they keep on saying, brows furrowed, indignant, angry, even, that “things have never been better!” You idiots! Don’t you get it? It’s funny, because the disjuncture is so…big…clear…obvious. The question then is: why?

When I look at the world, here’s what I see.

People don’t have much left to believe in. Let me offer you a few observations. Because I don’t mean that in a trivial way.

Look at all the world’s major religions. What do we see? Something striking. Huge pulses of fundamentalism are sweeping through them. All of them. From humble Christianity to gentle Buddhism to noble Hinduism — all religions which prize, of course, peace. And yet they’re all marred by fundamentalism, which is becoming, increasingly, violence, brutality, even hate. I don’t have anything against a single religion — I believe, if anything, in aspects of all of them, a universal creator and a universal creation. But there are healthy and unhealthy forms of faith and belief. To see all the world’s religions all plunging into fundamentalism at once? It tells us something.

It tells us that people are desperate for something to believe in. We can see the same dynamic at work very, very clearly almost everywhere that we look. Think of the way that technologists have turned technology into a religion of its own now, where you’ll get uploaded to the God-cloud and live forever. See the way that people defend their viewpoint almost theologically these days — with little regard for facts and reason. Look at the way that trust in institutions and systems has collapsed — and again, that’s global, not just in America. Look at the way that nationalism is surging and becoming outright fascism — again, a quest for belief in something.

Everywhere I look, I see people desperately searching for something — anything — to believe in. People turn to conspiracy theories, of absurd kinds — the Illuminati drink kids’ blood! They doomscroll online. They adopt identity politics — on left and right — as if it were the only thing that mattered at all, from “mens rights” onwards. Think of the way that incels — lonely young men — have created their own bizarre systems of belief in which they’ll smash their faces (I’m not kidding, here’s a link) to “looksmaxx,” or maximize their looks, because only “Chads” get “Stacys,” meaning bulging musclemen “get” girls, and all this is backed up by pseudo-biological theories of Darwinian fitness. I could go on literally for a whole books’ worth of examples.

Yet all that just raises the next question. If there’s little left to believe in…what was there to believe in? Well, of course, once upon a time, there was religion and king and country. Then came modernity, and things…changed. Then we were to believe in democracy. Its values of truth, justice, freedom, in literal senses, like inalienable rights for all. We were to believe in “the future” — the idea that technology would makes our lives better, in an almost linear way. We were to believe in progress, which was the march of all that, in a thing called “the economy” — which was no longer just 99% of people of peasants, giving half their harvest to the 1% who called themselves of “noble” blood — but all of that, democracy, freedom, technology, progress, combined, into this new abstraction.

That’s a lot of things to believe in, and the problem is that they are all failing. And when we look at the causal chain, the rot starts from the last link, the most crucial one, the things all those others combine into — the economy. Everywhere, people are growing fearful, and I mean genuinely afraid, of what happens next. That’s true in America, Europe, Asia, around the world. And so pessimism isn’t just rising — it’s exploding — everywhere.

And so all that comes back to an even deeper set of issues. Progress is now stalling, for the first time in centuries. We have hit one of human history’s greatest inflection points — and yet barely anyone even talks about it. That’s probably because pundits who write books about how great things are can hardly sell them if they acknowledge the fact that progress is now stalling and going into reverse. And yet when you understand that, pessimism’s hardly difficult to understand, is it?

So in what way is progress stalling out and reversing? Let’s review a bit of history for a second. It was a wave of great thinkers who warned that as human civilization did this new thing called “industrialization,” there was going to be a price to be paid.

John Ruskin warned of the loss of connection with nature. Novelists like Dickens warned of the loss of community, of poverty and inequality amidst plenty — and of the perversion of virtue itself, like greed becoming “good.” Durkheimwarned of strange, new social illnesses, like “anomie,” his term then for what we’d call today depression and anxiety and suicidality, born of loneliness. Sartre wrote about ennui, the sense of meaninglessness, as this vast machine chugged around you. Marx, of course, warned of alienation and immiseration — by which he meant being alienated from one’s self, not just from others, and being conditioned to accept it all there was. Freud warned, of course, of “neurosis” itself rising — the human psyche becoming disordered, and minds like Adler warned its libido, its fundamental drive to live, was warped by all these new, unfamiliar pressures, constrictions, restrictions. Orwell, of fanaticism, violence, conformity, the perversion of society itself.

What do you see today? What I see is that the warnings of all these great minds have borne fruit. It didn’t have to be the case that these minds were right. They could have just been idly theorizing, or telling stories. But when you look at our societies now — having undergone this centuries long process of industrialization — it’s hard to dispute that their warnings did something remarkable: they came true.

I say that’s remarkable because we’re now at the end of the process of industrialization. These minds are long dead. But they saw this deep into our future, the shared journey of human civilization. And they were that right.

Their predictions of the price of human progress have been eerily, remarkably accurate. Durkheim predicted that societies would develop a condition called anomie, the loss of social bonds, ruptured by ways of life in which everything but money, basically, was disposable, right down to people and relationships themselves. Look at America. Today, it has a “loneliness epidemic,” and Americans…don’t have…friends.

Think about Dickens’ warnings — and tell me our societies don’t resemble his novels, still, in their portrayals of not just inequality, but the brutal struggle just to endure it. Think about the way Marx — and no, this doesn’t make you a Marxist, you don’t have to believe in the Communist Revolution — warned of alienation and immiseration, and see how people doomscroll, don’t know what do with their fear and worry, about never having enough, and fail to lift one another up. Think of how crazy our societies appear to be going, with lunacy, extremism, fanaticism, and think of Freud’s warnings of neurosis — or Adler’s warnings that the death drive might take over, as people gave up on living.

I could go on. Perhaps you see the theme. These are all just flavors, facets, shades of what we call — all too inaccurately — pessimism, aren’t they?

Yet it was Ruskin, perhaps, who’s warnings have come truest, and is still the most overlooked on this list of great minds. He warned of a loss of communion with nature, even a kind of total blindness to it — and here we are, killing the planet, and not giving much of a damn. Ask the average person, and they can name ten celebrities or instafluencers in a heartbeat…but not a single one of the planet’s tipping points, which we’re now hitting. Tell me Ruskin wasn’t eerily correct.

That, too, is a kind of pessimism. This loss of…connection. Isn’t that what we’re talking about, really? Think of the list above. A loss of connection with….each other. With history. With our minds and bodies. With our spirits. With ourselves. With nature, which is to say, life itself. Tell me that loss of connection isn’t profound, omnipresent, oppressing, shattering, when you really notice it. How many people do you see that feel connected to any of those things? Mostly, those who do feel connected to something…well…it’s not a grand and noble and true thing, like on the list above, it’s…a demagogue…a Trump…their brand…their empty promises…the cheap thrill of hate they deliver when they rage at those they think of inferior…maybe some celebrity…a conspiracy theory…some bizarre belief system whether its what incels come up or the “transhumanists” do…the idea that my blood is superior to yours…that there’s some kind of secret group conducting a great “replacement” on the pure and true.

See how all these things are connect…ed? How the loss of connection the timeless triggers a kind of frantic implosion in the human psyche…which begins with fundamentalism, of all kinds…proceeds through ignorance…and ends in violence and brutality…as the witch-burnings begin?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to HAVENS to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.