How Nepo Babies Teach Us What Went Wrong With the Economy

In a Downwardly Mobile Society, Watching Opportunities Flow Upwards….Sucks

There’s a phrase that’s been on lips for the last month or two. “Nepo babies.” Have you heard it? It means basically kids of the rich and famous and powerful, who make it, because, well, mommy or daddy are there to give them not just a leg up, but more like a jetpack which means they can rocket up the ladder, past everyone else, grinning coyly and waving “bye!” back down, the whole way.

The idea of “nepo babies” has become a cultural touchpoint recently, a kind of new absurdist joke about our societies and our world, black comedy, satire-meets-reality. It’s provoked firestorms across front pages and gossip blogs both. And yet it’s blackly funny precisely because, well, it’s all too revealing. Of where our societies and economies really are. “Oh, they’re a nepo baby.” Explains a lot. There’s more truth to this little phrase, then, than might meet the eye.

The fact is that “nepo babies” are a symptom, a classic feature, of societies in decline, and economies that are going the wrong way. How so?

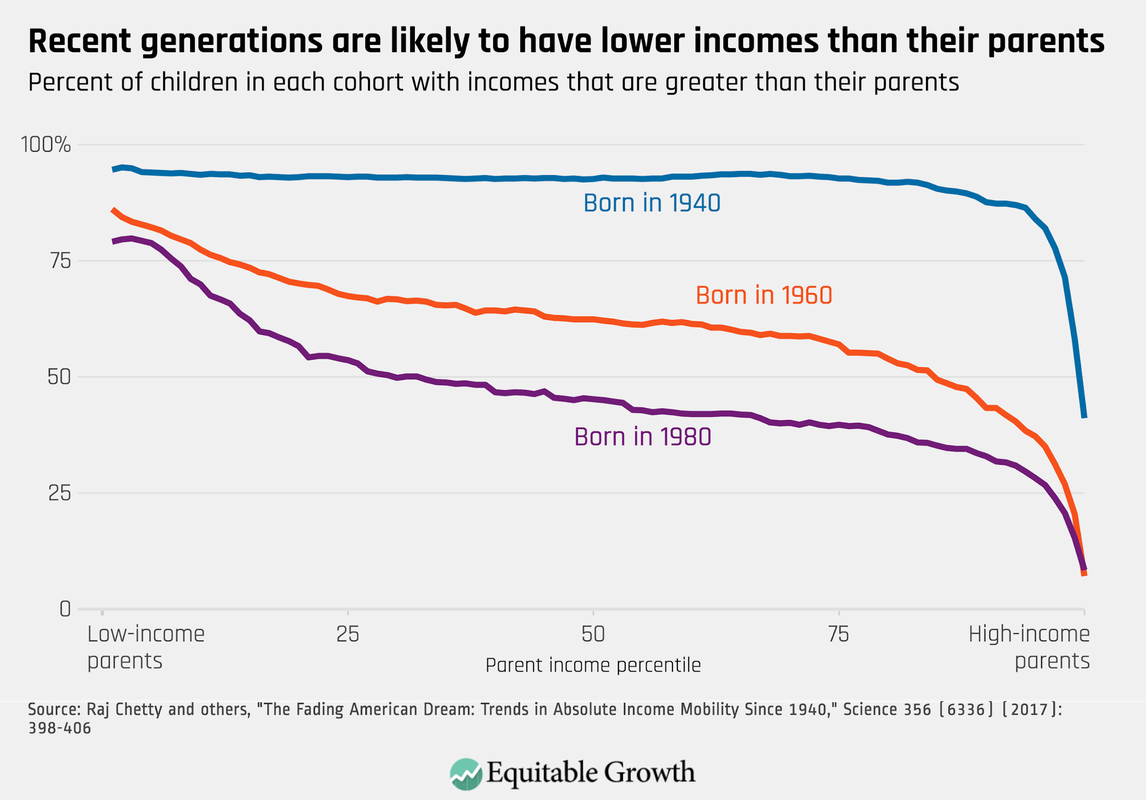

Take a hard look at our societies. What’s the first thing you see? The most vivid fact the economist in me sees is this: we now have four to five generations in downward mobility. Four to five generations. Gen X did worse than Boomers, and it was kind of funny, Millennials did worse than Gen X, and it wasn’t that funny anymore, Zoomers are doing worse than Millennials, and it’s dire, grim, and a little panic-inducing, if you’re a parent.

The great socioeconomic trend of our time, in other words, is downward mobility. Downward mobility explains a lot — and predicts it, too. Men, lashing out, in rage, not getting the jobs, money, sexual partners, relationships they feel entitled to, because that’s what they’ve been told all their lives they deserve, will magically come their way? To the point of massacres? Downward mobility. Or how about the fact that our societies are increasingly indebted: that’s another feature, because of course as generations get poorer, public purses shrink, and so do, well, household ones, and both societies and people have to borrow just to stay afloat. Downward mobility strikes again.

But there’s another effect of downward mobility — a set of effects, really — which are a little less well know, more hidden. Let’s put them under the heading of “a return to dynasties.” Dynasties. For a very, very long time, they weren’t just a feature of human society, they were its linchpin, its organizing force. The head most powerful dynasty in society became the “king” or “emperor,” the next ones down the ladder became “nobles,” and so forth. Dynasty, of course, is intimately wrapped up with patriarchy, because at least in most Western societies, dynastic privileges — inheritance of land, money, titles which conferred status and power — went to the first born son, and passed down the line that way.

Why does downward mobility produce a regression to dynastic forms of social order? Well, for a very simple reason. Everyone else’s boat is sinking. Except the wealthy and powerful, who are often only gaining, because by now economies have become zero, or even negative, sum games — meaning that for someone to win, someone else has to lose. Think about it: what does “downward mobility” really mean? It means a lack of opportunities, chances, shots. For me to win, someone else has to lose.

So. In downwardly mobile societies, what’s really shrinking is opportunity itself. Sure, there’s always going to be the kind of guy who interjects at this juncture and says, beating his chest, “But I made it all by myself!!” Sure, dude. You build those roads and invented the alphabet and printed the very first first note of currency in human history. All by yourself, huh? Nobody does anything all by themselves, from having a baby to…fulfilling any aspect of their potential. Opportunities shrink in downwardly mobile societies, meaning there are less, less good, and less stable ones. Of course for things we usually associate with the term — careers, jobs, degrees, and so forth. But also for the hidden, more intimate stuff of life: relationships. Networks. Friends.

Check out how many Americans don’t have any close friends. Ready for a surprise? It’s 12%. More than 1 in 10 people. That’s because they’re usually busy working too hard to afford luxuries like friendship. And that’s a number that has quadrupled in the last thirty years.

Are you seeing how “nepo babies” begin to emerge? Let’s crystallize a bit of that. Downwardly mobile societies leave the average person, the average household, struggling to stay afloat. Each generation does worse than the last. Meanwhile, that’s precisely because economies have turned into zero or negative sum games — for me to win, you have to lose, three people have to lose, ten have to lose.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to HAVENS to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.